Sidereal time

Sidereal time /saɪˈdɪəriəl/ is a time-keeping system astronomers use to keep track of the direction to point their telescopes to view a given star in the night sky. Briefly, a sidereal day is a "time scale that is based on the Earth's rate of rotation measured relative to the fixed stars."[1]

From a given observation point, a star found at one location in the sky will be found at nearly the same location on another night at the same sidereal time. This is similar to how the time kept by a sundial can be used to find the location of the Sun. Just as the Sun and Moon appear to rise in the east and set in the west, so do the stars. Both solar time and sidereal time make use of the regularity of the Earth's rotation about its polar axis, solar time following the Sun while sidereal time roughly follows the stars. More exactly, sidereal time follows the vernal equinox, which is not quite fixed among the stars; Precession and nutation shift the equinox slightly from one day to the next, so sidereal time is not an exact measure of the rotation of the Earth relative to inertial space.[2] Common time on a typical clock measures a slightly longer cycle, accounting not only for the Earth's axial rotation but also for the Earth's annual revolution around the Sun of slightly less than 1 degree per day.

A mean sidereal day is about 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.091 seconds (23.93447 hours or 0.99726957 mean solar days), the time it takes the Earth to make one rotation relative to the vernal equinox. (Due to nutation, an actual sidereal day is not quite so constant.) The vernal equinox itself precesses slowly westward relative to the fixed stars, completing one revolution in about 26,000 years, so the misnamed sidereal day ("sidereal" is derived from the Latin sidus meaning "star") is some 0.008 seconds shorter than the Earth's period of rotation relative to the fixed stars.

The longer "true" sidereal period is called a stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). It is also referred to as the sidereal period of rotation.

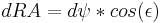

Maps of the stars in the night sky use declination and right ascension as coordinates. These correspond to latitude and longitude respectively. While declination is measured in degrees, right ascension is measured in units of time, because it was most natural to name locations in the sky in connection with the time when they crossed the meridian.

In the sky, the meridian is the imaginary north to south line that goes through the point directly overhead (the zenith). The right ascension of any object crossing the meridian is equal to the current local (apparent) sidereal time, ignoring for present purposes that part of the circumpolar region north of the north celestial pole (for an observer in the northern hemisphere) or south of the south celestial pole (for an observer in the southern hemisphere) that is crossing the meridian the other way.

Because the Earth orbits the Sun once a year, the sidereal time at any one place at midnight will be about four minutes later each night, until, after a year has passed, one additional sidereal day has transpired compared to the number of solar days that have gone by.

Contents |

Sidereal time and solar time

Solar time is measured by the apparent diurnal motion of the sun, and local noon in solar time is the moment when the sun is at its highest point in the sky (exactly due south or north depending on the observer's latitude and the season). The average time for the sun to return to its highest point is 24 hours.

The Earth makes a rotation around its axis in a sidereal day; during that time it moves a short distance (about 1°) along its orbit around the sun. So after a sidereal day has passed the Earth still needs to rotate a bit more before the sun reaches its highest point. A solar day is, therefore, nearly 4 minutes longer than a sidereal day.

The stars are so far away that the Earth's movement along its orbit makes nearly no difference to their apparent direction (see, however, parallax), and so they return to their highest point in a sidereal day.

Another way to see this difference is to notice that, relative to the stars, the Sun appears to move around the Earth once per year. Therefore, there is one fewer solar day per year than there are sidereal days. This makes a sidereal day approximately 365.24⁄366.24 times the length of the 24-hour solar day, giving approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.1 seconds (86,164.1 seconds).

Precession effects

The Earth's rotation is not a simple rotation around an axis that would always remain parallel to itself. The Earth's rotational axis itself rotates about a second axis, orthogonal to the Earth's orbit, taking about 25,800 years to perform a complete rotation. This phenomenon is called the precession of the equinoxes. Because of this precession, the stars appear to move around the Earth in a manner more complicated than a simple constant rotation.

For this reason, to simplify the description of Earth's orientation in astronomy and geodesy, it is conventional to chart the positions of the stars in the sky according to right ascension and declination, which are based on a frame that follows the Earth's precession, and to keep track of Earth's rotation, through sidereal time, relative to this frame as well. In this reference frame, Earth's rotation is close to constant, but the stars appear to rotate slowly with a period of about 25,800 years. It is also in this reference frame that the tropical year, the year related to the Earth's seasons, represents one orbit of the Earth around the sun. The precise definition of a sidereal day is the time taken for one rotation of the Earth in this precessing reference frame.

Definition

Sidereal time, at any moment (and at a given locality defined by its geographical longitude), more precisely Local Apparent Sidereal Time (LAST), is defined as the hour angle of the vernal equinox at that locality: it has the same value as the right ascension of any celestial body that is crossing the local meridian at that same moment.

At the moment when the vernal equinox crosses the local meridian, Local Apparent Sidereal Time is 00:00. Greenwich Apparent Sidereal Time (GAST) is the hour angle of the vernal equinox at the prime meridian at Greenwich, England.

Local Sidereal Time at any locality differs from the Greenwich Sidereal Time value of the same moment, by an amount that is proportional to the longitude of the locality. When one moves eastward 15° in longitude, sidereal time is larger by one sidereal hour (note that it wraps around at 24 hours). Unlike the reckoning of local solar time in "time zones," incrementing by (usually) one hour, differences in local sidereal time are reckoned based on actual measured longitude, to the accuracy of the measurement of the longitude, not just in whole hours.

Apparent Sidereal Time (Local or at Greenwich) differs from Mean Sidereal Time (for the same locality and moment) by the Equation of the Equinoxes: This is a small difference in Right Ascension R.A. ( ) (parallel to the equator), not exceeding about +/-1.2 seconds of time, due to nutation, the complex 'nodding' motion of the Earth's polar axis of rotation. It corresponds to the current amount of the nutation in (ecliptic) longitude (

) (parallel to the equator), not exceeding about +/-1.2 seconds of time, due to nutation, the complex 'nodding' motion of the Earth's polar axis of rotation. It corresponds to the current amount of the nutation in (ecliptic) longitude ( ) and to the current obliquity (

) and to the current obliquity ( ) of the ecliptic, so that

) of the ecliptic, so that  .

.

Greenwich Mean Sidereal Time (GMST) and UT1 differ from each other in rate, with the second of sidereal time a little shorter than that of UT1, so that (as at 2000 January 1 noon) 1.002737909350795 second of mean sidereal time was equal to 1 second of Universal Time (UT1). The ratio varies slightly with time, reaching 1.002737909409795 after a century.[3]

To an accuracy within 0.1 second per century, Greenwich (Mean) Sidereal Time (in hours and decimal parts of an hour) can be calculated as

- GMST = 18.697374558 + 24.06570982441908 * D ,

where D is the interval, in UT1 days including any fraction of a day, since 2000 January 1, at 12h UT (interval counted positive if forwards to a later time than the 2000 reference instant), and the result is freed from any integer multiples of 24 hours to reduce it to a value in the range 0-24.[4]

In other words, Greenwich Mean Sidereal Time exceeds mean solar time at Greenwich by a difference equal to the longitude of the fictitious mean Sun used for defining mean solar time (with longitude converted to time as usual at the rate of 1 hour for 15 degrees), plus or minus an offset of 12 hours (because mean solar time is reckoned from 0h midnight, instead of the pre-1925 astronomical tradition where 0h meant noon).

Sidereal time is used at astronomical observatories because sidereal time makes it very easy to work out which astronomical objects will be observable at a given time. Objects are located in the night sky using right ascension and declination relative to the celestial equator (analogous to longitude and latitude on Earth), and when sidereal time is equal to an object's right ascension the object will be at its highest point in the sky, or culmination, at which time it is usually best placed for observation, as atmospheric extinction is minimised.

Sidereal time is a measure of the position of the Earth in its rotation around its axis, or time measured by the apparent diurnal motion of the vernal equinox, which is very close to, but not identical to, the motion of stars. They differ by the precession of the vernal equinox in right ascension relative to the stars.

Earth's sidereal day also differs from its rotation period relative to the background stars by the amount of precession in right ascension during one day (8.4 ms).[5] Its J2000 mean value is 23h56m4.090530833s.[6]

Exact duration and its variation

A mean sidereal day is about 23 h 56 m 4.1 s in length. However, due to variations in the rotation rate of the Earth, the rate of an ideal sidereal clock deviates from any simple multiple of a civil clock. In practice, the difference is kept track of by the difference UTC–UT1, which is measured by radio telescopes and kept on file and available to the public at the IERS and at the United States Naval Observatory.

Given a tropical year of 365.242190402 days from Simon et al.[7] this gives a sidereal day of 86,400 ×  , or 86,164.09053 seconds.

, or 86,164.09053 seconds.

Aoki et al.,[8] defined UT1 such that the observed sidereal day at the beginning of 2000 would be ⅟1.002737909350795 times a UT1 day of 86,400 seconds, which gives 86,164.090530833 seconds of UT1. For times within a century of 1984, the ratio only alters in its 11th decimal place. This web-based sidereal time calculator uses a truncated ratio of ⅟1.00273790935.

Because this is the period of rotation in a precessing reference frame, it is not directly related to the mean rotation rate of the Earth in an inertial frame, which is given by ω=2π/T where T is the slightly longer stellar day given by Aoki et al. as 86,164.09890369732 seconds.[6] This can be calculated by noting that ω is the magnitude of the vector sum of the rotations leading to the sidereal day and the precession of that rotation vector. In fact, the period of the Earth's rotation varies on hourly to interannual timescales by around a millisecond,[9] together with a secular increase in length of day of about 2.3 milliseconds per century, mostly from tidal friction slowing the Earth's rotation.[10]

Sidereal days compared to solar days on other planets

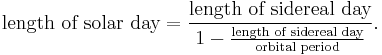

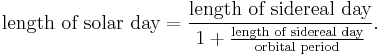

Of the eight solar planets,[11] all but Venus and Uranus have prograde rotation—that is, they rotate more than once per year in the same direction as they orbit the sun, so the sun rises in the east. Venus and Uranus, however, have retrograde rotation. For prograde rotation, the formula relating the lengths of the sidereal and solar days is

or equivalently

On the other hand, the formula in the case of retrograde rotation is

or equivalently

All the solar planets more distant from the sun than Earth are similar to Earth in that, since they experience many rotations per revolution around the sun, there is only a small difference between the length of the sidereal day and that of the solar day—the ratio of the former to the latter never being less than Earth's ratio of .997 . But the situation is quite different for Mercury and Venus. Mercury's sidereal day is about two-thirds of its orbital period, so by the prograde formula its solar day lasts for two revolutions around the sun—three times as long as its sidereal day. Venus rotates retrograde with a sidereal day lasting about 243.0 earth-days, or about 1.08 times its orbital period of 224.7 earth-days; hence by the retrograde formula its solar day is about 116.8 earth-days, and it has about 1.9 solar days per orbital period.

By convention, rotation periods of planets are given in sidereal terms unless otherwise specified.

See also

- Earth rotation

- Sidereal month

- Synodic day

- Anti-sidereal time

- Nocturnal (instrument)

- Transit instrument

References

- ^ National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST], Time and Frequency Division. "Time and Frequency from A to Z." http://www.nist.gov/pml/div688/grp40/enc-s.cfm

- ^ P K Seidelmann (ed.) (1992), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, page 48.

- ^ P K Seidelmann (ed.) (1992), Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, at page 52 (and at page 698).

- ^ Approximate sidereal time (US Naval Observatory).

- ^ Seidelmann, p. 48.

- ^ a b Aoki, S., B. Guinot, G. H. Kaplan, H. Kinoshita, D. D. McCarthy and P. K. Seidelmann: "The new definition of Universal Time". Astronomy and Astrophysics 105(2), 359-361, 1982.

- ^ Simon, J. L., P. Bretagnon, J. Chapront, M. Chapront-Touzé, G Francou and J. Laskar: "Numerical expressions for precession formulas and mean elements for the moon and the planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics 282, 663-683, 1994.

- ^ Aoki, S., B. Guinot, G. H. Kaplan, H. Kinoshita, D. D. McCarthy and P. K. Seidelmann: "The new definition of Universal Time". Astronomy and Astrophysics 105(2), 361, 1982, see equation 19.

- ^ Hide, R., and J. O. Dickey: "Earth's variable rotation". Science 253 (1991) 629-637.

- ^ Stephenson, F.R. Historical eclipses and Earth's rotation. Cambridge University Press, 1997, 557pp.

- ^ Bakich, Michael E., The Cambridge Planetary Handbook, Cambridge University Press, 2000; ISBN 0-521-63280-3.

- P. Kenneth Seidelmann, ed., Explanatory supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, (Mill Valley, Cal.: University Science Books, 1992)

External links

- Web based Sidereal time calculator

- Build an internet synchronized sidereal clock

- For more details, see the article on sidereal time from Jason Harris' Astroinfo.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||